Painting sheds light on Burnley’s past

The article is inspired by the incompetence of the County Council’s Highways, and their contractors, who conspired to increase my journey time on Monday and Wednesday of last week, by over two hours.

That I managed to get to my destinations on time was no thanks to them. It took a good deal of forward planning which I might not have minded had I, and others in Burnley, been kept abreast of events at Gannow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt seems to me that the delays engendered by this work, and at other nearby sites, is worse than I remember it was when the nearby M65 was under construction! However, having met, in the company of Mr Tony Mitchell, the Chairman of the Towneley Hall Society, a charming couple from Addingham who had an interesting painting of Old Burnley to show us, I decided to write about a subject relating to the painting.

The painting was by an artist, possibly local, by the name of Wood (or Woods) and was of Union Street. The medium used was water colour and the image showed Union Street’s houses, the “Bank of England” shop in Brown Street with the spire of St James’s Church in the background.

Unfortunately, I have not got a copy of the painting but the four of us visited the site. Of course Union Street is no longer, as it was one of the many older properties demolished as long ago as the 1930s. The street is now the site of Burnley’s Telephone Exchange but there was still plenty for Tony and myself to show our visitors.

On the other hand, it transpired there was plenty to interest them. We noticed that the stone setts of Orchard Bridge, which are shown in the painting, were still there, sturdy granite blocks which do not seem to have decayed, even a little, since the artist was at work. I took our visitors round the corner to Blackburn Street (the location of Cuckoo Mill, which is now up for sale) but, more importantly, the site of the last of the old cottages in this part of town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis cottage is part of a block now occupied by a small garage business and, though it is much changed, enough of the original building can be seen to show what it once looked like. To me, it is a little gem that has survived all the demolition that has taken place here over the past 80 or so years.

The four of us explored the area pretty thoroughly finding that more than I had supposed has survived. However, this was little enough and I got to thinking that it is a pity more people did not take photos (or undertake paintings) of areas declared to be unfit for human habitation before they were demolished. We discussed why it was that Mr (?) Wood felt it necessary to paint the picture and tried to assess how accurate was his depiction.

Back home, I looked to see if there was a Wood living in Union Street just before it was demolished. In 1927 to 1928 there were 10 occupied houses in Union Street, though it was clear several of the properties were no longer lived in. Unfortunately, none of the heads of household, as listed in the Commercial Directory for that year, was called Wood.

It was then I decided to look further afield and at John Street, which I knew (or thought I knew) was nearby, I found a J. Wood who was an overlooker in a cotton mill. Of course, this does not prove anything but I was dismayed when I noticed this John Street was in Habergham Eaves, not Burnley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

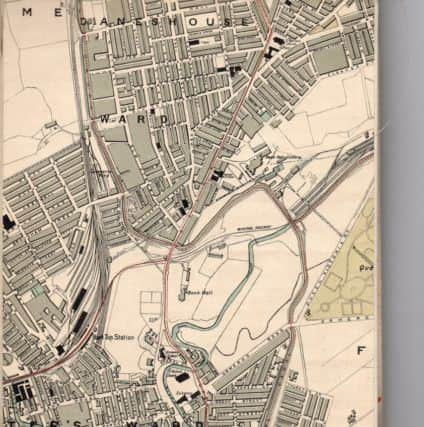

Hide AdThe John Street, near Union Street, was a narrow street of back-to-back houses parallel to Veevers Street and Gas Street which are both still there, accessed off Brown Street, which itself is off (Lower) St James’s Street. However, the John Street, for which I had the information, was clearly not the John Street of Burnley. The 1851 map shows us there were only eight houses on the Burnley street, whereas there were about 29 houses on the one in Habergham, which I think was in the George IV area.

Only a few days later, there was something of a coincidence. I met one of my colleagues, Mr Ramon Collinge, of Burnley Civic Trust. We had arranged to visit the church of St John’s in Cliviger with a view to writing a history of the church as a contribution to the forthcoming celebrations associated with the current work to restore that fine building. At the meeting, Ramon gave me some interesting documents some of which related to Burnley’s John Street.

The documents included the 1841 and 1851 Census Returns for the street, a copy of the 1851 map of the area and an analysis of some of the origins of residents of the street.

For those of you who have not gathered where John Street was, there is precious little of it left these days to remind you of its existence. John Street was a short cul-de-sac off Calder Street which, in the early 19th Century was off Cheapside rather than the St James’s Street that Cheapside became. Parallel to Calder Street, which is still there, is Brown Street and between the two ran Gas, Veevers, Union and Blackburn Streets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn Street was not a “through street” but was parallel to both Gas Street and Veevers Street. You will know that the Brown Street plot, between Gas Street and Veevers Street, is occupied by an industrial building, formerly Stanworth’s, now part of the Merc Group. John Street was behind the building occupied by the present Merc Group.

The street contained six small houses which were back-to-back with Veevers Street and at least another two which were back-to-back with Gas Street. It could be that there were more on this side but they are not shown in the 1851 map.

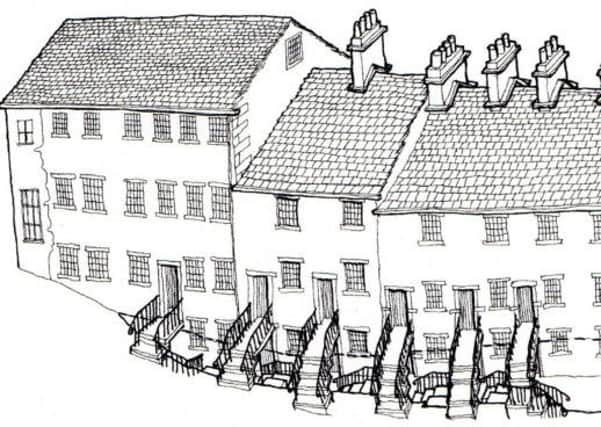

From Veevers Street you can see the remains of some of these houses to this day and John Lowe, who formerly worked at Burnley Council, produced a drawing of them which I publish with this article. As you can see, the industrial building is to the left. It served as a textile mill as early as the 1790s. The houses are to the right and John has recreated the accesses to them as they were when the properties were occupied. The dotted line indicates the natural level of the land but, if you decide to have a look at the site today, there is quite a lot to see of the houses which are reconstructed in John’s illustration.

John Street was on the other side of these properties. It was accessed from Calder Street which, even today, is to the right of these buildings, but unfortunately, we have no drawings of the street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe do know who lived there in 1841. In that year there were 12 houses occupied by 43 people all of whom were born in Lancashire. The importance of this will be noted later. Most of those whose occupations are listed were connected with the textile industry, mainly in cotton but there were two wool combers. There were also two pipe makers, in different households, and three coal miners, all of them in the same household. In addition, there was a single block printer and a hatter.

If we turn to John Street, as it was in 1851, a number of changes are noted. The first is that there has been a considerable turn around in family names. There are Kelleys, Binnes, Deaseys, Gaughtons, Walshes, Murphys, Maloys, Roughams and a single Mulrooney, a single Nulton, a single Moroon and a single Shay. All of these were new to the street and from Ireland. Whole households (remember they were tiny cottages) are occupied by generally very young Irish, sometimes more than one family in the same household.

This, of course, was a consequence of the Irish Potato Famine that had taken place in the 1840s when thousands of Irish people were forced to leave their homeland in search of work in Britain and on the other side of the Atlantic.

It might be instructive to look in detail at one of these houses. It is listed as 4 John Street and had three rooms at the most. The head of the household was Patrick Walsh who, like all the others at this address, was born in Ireland. He was 60 years of age and is described as an agricultural labourer. His wife Mary was a washerwoman. John Walsh (son, 20) was also an agricultural labourer; Mary (daughter, 17) was a rover on a cotton mill, another son also worked in a mill and two more sons were described as scholars.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the same house, James Murphy was a lodger, unmarried, aged 20 and was a mason’s labourer. There were two more Murphys, also described as lodgers, both teenagers, one a cripple, the other a doffer in a cotton mill. To complete the household there were two more lodgers, Bridget Mulrooney (18), a creeler in a cotton mill, and Michael Nulton (27), a mason’s labourer. Altogether there were 12 people in this household.

Just about all of the jobs held by Irish workers on the street were low skilled and low paid, though a few were throstle spinners. One, Margaret Shay, is described as a “pauper, charwoman”. So far as I can see, only one of the 1841 families was still living in John Street in 1851. This is the Hornby family, the head of the household, John, aged 46 and described as a block printer, presumably in the calico trade. There is a little uncertainty about John because, in the 1841 Census, he is down as James.

You might not be surprised to learn that the total number of people living in John Street in 1851 was up considerably on the 43 that lived there in 1841. There were, in fact, 66 people living in the street in 1851.

Another of the changes, between the 1841 and 1851 censuses, is that, in 1851, we have a little more detail about the houses in John Street. Some properties are listed with half numbers. This usually means these houses were cellar dwellings and, if you look at John Lowe’s drawing, you can see how that might be. Altogether there were five properties with half numbers listed and they had eight, three, two, three and two residents respectively. Needless to say, the property with eight residents was occupied by five members of the Deasey family and three Gaughtons, all Irish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA number of things came together to make this article possible. I have been pleased to write it because one of the criticisms levelled at me is that I do not write enough about our local social history. This is much more difficult to achieve in Burnley, but I do try my best to give you as much variety, given the resources available, as I can.

I have written before that it is one of my intentions to undertake a proper study of this area of Burnley. It is the part of town that contained the Club Houses, the property which lent its name to Union Street with which I started this article. Union Street came about because of the Hall Union Club, the terminating building society which built much of the housing in this area. I will return to this subject at a later date.